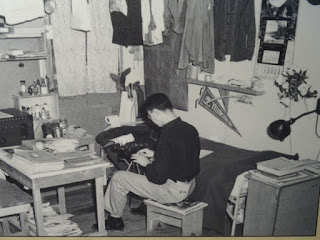

Candid photo of actual family room

Today, little remains

physically of the structures at Heart Mountain. There are a couple of buildings

and a smokestack of the hospital complex and a barrack building that has

recently been donated and moved back to the site. None of the buildings are open for

visitors. There is a memorial site and

observation posts on top of a hill from which visitors can get a little idea of

how the camp was set up. There is an excellent interpretive center with

interesting and well done exhibits showing life before Pearl Harbor, the

deportations and life in the camp.

But

this is not an “On the Road” Histocrats blog; I’m writing to share an

experience at the interpretive center that made me really think about history

and the teaching of history. While we were in the museum, a family of three

came in: an older Japanese-American man, his Caucasian wife, and their

granddaughter who appeared to be in her twenties. It’s a relatively small museum, so we

couldn’t help but overhear their conversation with the museum staff. Turns out, the man was an internee at Heart

Mountain as a small boy, and this was his first visit there since 1945. The museum staff immediately asked if he

wanted to give them his contact information so that his oral history could be

added to their collection. He quietly

refused, saying he wasn’t interested.

His wife and granddaughter said that he had never spoken about his

experiences, that one of the cultural characteristics of Japanese people is not

to dwell on the past, especially unpleasantness, and that had been drilled into

him by his family.

The

family followed us into the theater for the excellent film about the camp; the

film was produced by the son of an internee and features about a dozen internees

telling their stories, including a couple who lived in the same barracks block

as the visiting grandfather. Throughout the fifteen minute film and the museum

exhibits, I watched the grandfather.

While his granddaughter sobbed during the movie, he sat stoically,

without changing expression. That

stoicism persisted as he looked at photographs and exhibits, including

reproductions of the rooms. I could tell

that his stoicism frustrated his granddaughter, who obviously wanted him to

open up, and his wife, presumably after decades of marriage, appeared to be

resigned to his quietness.

When I

awoke early the next morning (body clock still on Georgia time), I thought

about what I had seen, and I wondered what if I should have introduced myself

to the family as a history teacher and told the grandfather how much his story

and first person accounts like his mean to my students. Every year, I bring in

Vietnam veterans to speak to my classes, and I often share stories of my

encounters with Holocaust survivors and civil rights activists. Their stories bring history to life for my

students, and they create more thought, discussion, and reflection than any

textbook or lecture can. However, I know

that there is a lot of history within people that they are reluctant to share,

so much pain that they can’t bear to speak it. Unfortunately, that grandfather

may never be able to share his story, but I developed a deeper appreciation for

those who have shared, and I have a renewed desire to use primary sources and

personal accounts in my class this fall.